Radio music & content research shows that great on-air personalities and hit music producers have one thing in common – they never keep their audience waiting for long.

Starting his career as on-air talent in 1985, Dan Cowen is now group PD for AlwaysMountainTime, a company running 11 radio brands in Colorado resort towns. Before that, he was VP of Research for Pinnacle Media Worldwide. In this interview, we talk about best practices for (and programming lessons based on) radio music & content research. ‘Get to the hook part fast.’

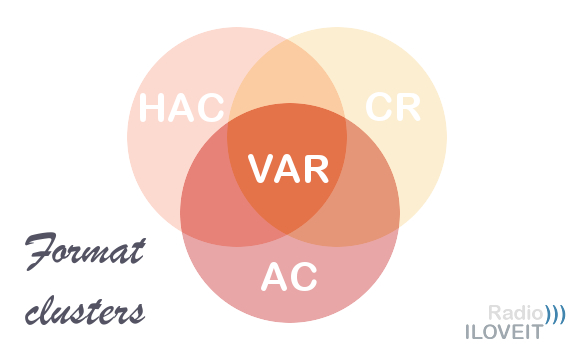

“It homogenises out these regional taste differences”

Airplay in other markets doesn’t relate to preferences of your local audience (image: amCharts / Thomas Giger)

Demand a research budget

“Research is absolutely critical to get the very best out of your radio station. The unfortunate thing about being a program director — or brand manager, as they are increasingly calling them in the US — is that you really are just that.” Cowen paints a somewhat disillusioned picture of a market that we all have looked up to for years. “I have a very good friend who is the operations manager for 5 stations, and the program director for 3 of those, and up until recently also did a daily 4-hour air shift. He’s in a medium market, where they’re making a ton of money for a large operator that owns hundreds of stations. But the days of having a marketing budget and research budget are long gone.”

Monitor airplay for inspiration

Monitor airplay for inspiration

Not having money for local research, his friend is using Mediabase to check the playlist of other stations — basically a digital, realtime version of printed trade magazines like Billboard or Radio & Records from the early days. When major-market radio brands with a similar format add a certain song or change its rotation, programmers in small and medium markets often follow the move, assuming that top stations have top research.

Follow the right stations

“The problem is: it becomes an echo chamber; everyone is doing the same.” Dan Cowen points out that those who rely on airplay services often don’t know the radio market, program director, and research policy of the stations they’re following. “They don’t know whether that station had a research project last week, or whether they haven’t had one in two years.”

And they often don’t know the music taste in that market. It’s probably different when you’re in Dallas than when you’re in LA.

“Absolutely, and that’s always been the case, but the problem is that the guy who’s programming in Dallas has a panel of stations that includes St. Louis, Chicago and LA, and another guy has a panel that includes Dallas, Cincinnati, Chicago and LA. They all go by what other people are doing, and it homogenises out these regional taste differences.”

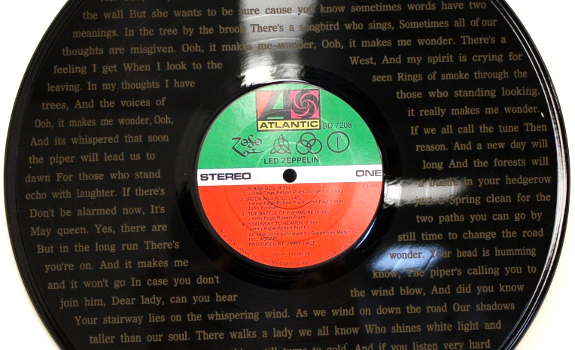

“People would listen for 6 hours a day, but there were only a 100,000 of them”

Creating 1 variety format based on 3 mainstream ones doesn’t guarantee long-term success (image: Thomas Giger)

Know where you stand

He also observes that when radio stations know (or assume) that their competition is not using research, they sometimes use it as an argument to not spend money on research either. “It now becomes a mutual disarmament. I’m sorry, but that’s crazy! I understand that $100,000 a year is onerous, even in big markets, these days. But talking to your wife’s friend who’s a big fan of a station, nah; that’s not research.” From his PD experience, he knows that research can give you peace of mind. “There are things that keep you up at night. Should I be more of this, or less of that? My competitor has just changed. Why did he do that? Maybe he has research showing I’m vulnerable, and I don’t know what that is?”

Have more than TSL

Have more than TSL

Cowen has seen a station with a great team, guided by good research, climb from #10 to #2 overall, and to #1 in women 25-54. “They are making bags of cash, right? A year and half later, the numbers wobble as the station doesn’t have a lot of cume, but relies on TSL. Three diary keepers or PPM users go on vacation, and all of a sudden, you look like hell! Because they were giving you lots of Time Spent Listening credit.”

Take listeners from competitors

Why was the station relying on TSL, and not on cume?

“They launched into a crowded marketplace as a variety format between AC, Hot AC and Classic Rock. There was an existing Classic Rock station getting decent female ratings, a Hot AC station, playing a lot of Pop music, getting good younger female numbers, and an AC station, playing a lot of Gold and softer music, getting good older female numbers.” It was decided to sit right in the middle of those 3 formats to attract a part of their female audience. The strategy worked at first. However, this variety mix was not a mass-appeal format: “They relied on people who would listen for 6 hours a day, but there were only a 100,000 of them as opposed to 1,000,000 people who give you 20 minutes a day.”

“You just can’t beat it”

Stairway to Heaven is still a great-testing song for many Classic Rock music formats (image: Gold Record Outlet)

Know what does(n’t) work

“A year and a half into this process, I asked: are you ready to do another research project? The PD answered: ‘I’d absolutely love to, but my company won’t pay for it. I know that I’m playing 85% of the right music; I just don’t know what the wrong 15% is’ — and that’s the key. It doesn’t take much if you’re a Pop station to play Can’t Stop The Feeling by Justin Timberlake. That is easy. But what do you put around it, and what’s the 15% of your playlist that is actively driving people away from your station, or no longer fits in the feel of it?” Dan Cowen sees that people’s music tastes are changing much faster today than 2 decades ago, also through the increased music exposure over the Internet, so the music cycle is moving faster.

Add some ‘wow’ spice

Add some ‘wow’ spice

“When you do a research project, you may find a vein of music that hasn’t been exposed for a while, where people say: ‘oh, wow; I like that; I missed that; those are songs I grew up with. I wanna’ hear Funky Cold Medina.’ You find that nobody in the market plays that song, and you play it — and because it tested so well, you maybe even play it as a Power. But then people hear it for the tenth time, and ‘oh, wow’ becomes: ‘oh, shit’…”

Know which songs last

The example makes clear that not every song has staying power, so continuous music research keeps you stay close to your target audience’s always-evolving music taste. Some songs survive 6 months, while others last forever: “Stairway to Heaven on a Classic Hits station; you just can’t beat it. Black Dog from Led Zeppelin; I’ve been waiting 35 years for that thing to die, haha.” Cowen explains that music research is not necessarily there to change your station; it also gives you confirmation when you’re right on track. You may have considered changes, but learn from research that they’re not necessary; that people still want to hear Pharrell Williams’ Happy, for example. If your competition hasn’t done research and decreases its rotation, assuming that people have enough of it, now you can get credits for playing it.

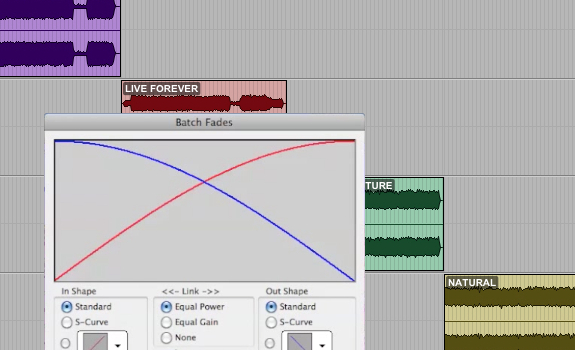

“Keeping all hooks at a limited duration will get participants into a natural rhythm”

Auditorium music tests with electronic dial measurement benefit from a flow montage (images: Pro Tools / AVID)

Keep research participants comfortable

He thinks that, basically, any research is decent research: “I’d rather have a paper-and-pencil music test than no music test at all.” A challenge he’s always had with auditorium music testing using a dairy, is that they feel like a school test to get a grade, or a personality test to get a job, where people want to perform well and want to give politically correct answers. His preference is to use a dial knob, and tell participants upfront that there are no right or wrong answers. “Look, I don’t need you to think; in fact, I don’t want you to think. I simply want you to create the perfect station for you.” To make it feel even more natural, hooks should not separated by a voice announcing ‘number 156’, ‘number 157’, and so on, but be part of an ongoing hook montage.

Appeal to listener emotions

Appeal to listener emotions

Dan Cowen has learned that emotions influence people’s listening behaviour. “How many times have you been listening, and your favourite song came on? And then, 3 seconds in, you touched the button for another station. Why would you do that? Because, at that moment, you felt like you needed something different. It’s sunny today, or it’s raining today; it’s almost weekend, or it’s Monday morning. Things like these form the way we’re using radio.”

Measure hook ending values

When using a dial, someone may move his dial up and down during a hook, instead of keeping it steady. Do you then use the average of that to determine that person’s rating?

“Especially with ‘hot button songs’ like Funky Cold Medina, you’ll see, as soon as the hook begins, that those who are most passionate about it, either positive or negative, instantly turn the dial, all the way up or down. Then the rest of the group, that is less passionate, begins to chime in, and it moderates. So we only count the last second of the hook.” Keeping all hooks at a limited duration (like 7 seconds for the most familiar songs, and 12 seconds for the least familiar songs) will get participants into a natural rhythm, so they can easily sense when their dial should be in its final position for that song.”

“If you spend too much time building up to the best part, people are not gonna’ be there”

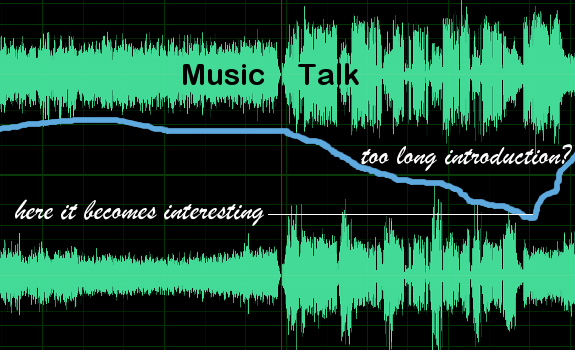

Catching the listener’s interest in the first 10-20 seconds of a bit is what you want (image: Adobe / Thomas Giger)

Help talents understand strategy

Cowen finds AMT sessions with real-time results (which staff members can follow on monitors in a separate room) a great occasion to get team backup for programming decisions. Disc jockeys who challenge their program directors and music directors about playing the same songs over and over, and discuss why other songs are played less often or being left out, can now see why. “If you have someone on your staff who’s been bugging you, make sure that you put a couple of his favourite songs in the test, and make sure that he’s sitting there on test night. So that when, after Black Dog by Led Zeppelin, you play that 4th track from this Jimi Hendrix album that he says is a masterpiece, he sees the graph diving for the bottom — and understands why you play Black Dog every 18 hours.”

Research more than music

Research more than music

It’s also educational to see what happens when jocks talk in between songs, especially when it’s over ‘dead air’. I guess the line goes down? :-)

“Haha, yes, but when we do content testing, everyone first has his dial around 50% on a 0 to 100% scale. We tell participants: anytime you hear something that’s funny, interesting, compelling, making you feel good, turn the dial up — and anytime you don’t like something, turn it down.”

Open content bits powerfully

Taking too much time for topic introduction is a common mistake that research has revealed. “While telling them: ‘last week, we were talking about this and that, then we got this person to tell us about it, and bla bla bla’, the lines keep going down, and down, and down… In those 30 seconds you spent on trying to set up a bit, 40 percent of the audience is gone; they never heard your great bit!” Dan Cowen’s advice is to hit 70% on the scale within the first 10-20 seconds by getting to the point as soon as you can. Hit producers of the 1960s figured this out early, so they would keep their songs short, and get to the hook (or chorus) part fast for a reason: “If you spend too much time building up to the best part of a song, people are not gonna’ be there, and you’re not gonna’ have a hit — even though you have a very good record.”

“Make them cry or make them laugh”

Touching people’s emotion is getting their attention – a great way of introducing your content (photo: stock image)

Trigger attention through emotions

He’s convinced that, with rare exception, “there’s no 2-minute radio bit that isn’t a better one at 90 seconds, and there’s no 90-second bit that isn’t a better one at 60 seconds. Websites have learned that if you add a 4-page post, even if it’s the most fascinating 4 pages you’ll ever read, there is a large segment of the audience that gets to your post, realises that it’s 4 pages, and won’t even begin reading it! I’m a fan of The Guardian’s website. They often use bullet points to summarise what you’re about to read, so that when you just want the facts, you can get them; when you want to read more, you can scroll down. As radio professionals, we have to realise that people are busy, and don’t really care that much – unless you make them care. Number 1 is emotion. Make them cry or make them laugh.”

Add Your Comment