How could radio add more variety, context and meaning to its playlist, and still keep its on-air music format focused? Some inspiration from music community Last.fm.

Matthew Hawn is Vice President of Product at the online music stream service Last.fm, your personal radio station that knows what you love and offers suggestions on what you might like as well. He explained how radio could use the same principles, during his recent speech at nextrad.io.

Radio’s own Discovery Channel

Does he consider Last.fm to be radio? “Absolutely. We’re a personalized form of radio. I believe strongly that radio is about discovery. It’s about introducing people to new bands, and the bands they forgot they liked.” Over the course of a decade, Last.fm has collected a huge amount of music data. Some facts about the personalized music service that CBS Radio bought in 2007 for 280 million dollars:

Last.fm community in numbers

- 35 million people currently have a Last.fm account

- 140 million people listen Last.fm through API services

- 72 million visitors/month, half of them are unique visitors

- 360 million pageviews/month are generated by the service

- 600 devices and services scrobble personal listening histories

- 800 scrobbles (music preference analyses) take place per second

- 57 billion pieces of music history have been collected in the past decade

- 13 million songs are ready to stream, another 90 million have been indexed

Connecting music interest groups

What makes Last.fm different from most social media, is that members don’t personally know each other. It’s anonymous and still familiar. “You make friends with your boss because you have to on Facebook… so there you have a weird social circle”, Matthew Hawn says. “Your neighbors on Last.fm are different. You may not know these people, but they are like you – it’s an interest connection instead of a social connection.

Matthew Hawn: “No computer algorithm can match a lyrical sense of what song comes next” (photo: Dan Smyth)

What is a playlist?

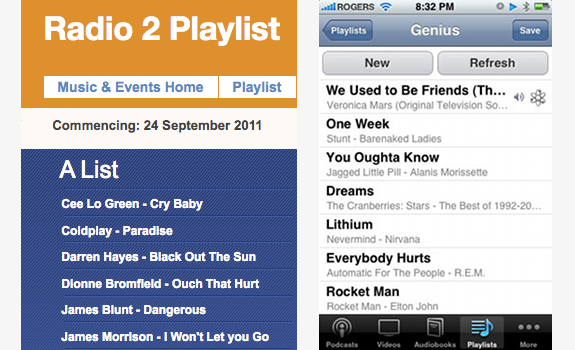

Most radio people consider a music schedule to be based on something like the BBC Radio 2 playlist. It is a selection of (contemporary) songs, put in a certain order by a music director based on the station’s format, audience research, gut feeling, and category rotations. Hawn: “The PDs that I know are great and they all love music, but there is a shift going on. For a new generation, this is a playlist” (he shows a picture of two smartphone based music apps).

A static playlist of BBC Radio 2 compared to a dynamic rundown in Genius (design: BBC, Genius)

Static vs. dynamic playlists

The picture above shows the interesting difference between old and new school music scheduling. One is static, the other dynamic; one is rational, the other intuitive; one is prepared, the other spontaneous. It makes clear that music directors and program directors still select music for a passive audience. Young listeners are active: they search and select music on different platforms, based on automated or social recommendations. “That gap between the two is at the heart of what we struggle with.”

Mix tapes become algorithms

Mix tapes become algorithms

Matthew Hawns favorite playlist is a mix tape. He remembers: “I was sitting next to my stereo, with the radio on and tried to press the record button at the right moment, praying that the deejay wouldn’t talk over the song and screw up my tape.” Rob Sheffield’s Love Is A Mix Tape is a book he recommends as a must-read. A lot has changed: today’s mix tape is based on an algorithm: code that creates music recommendations based on listening behavior.

Music defines social classes

“How you feed the algorithm is where the magic comes in”, he says. Last.fm is using a combination of social and textual data, but most importantly the user’s history. The output is “a combination of what you love and who you are – and I think that’s the heart of a playlist. People use music to badge themselves and to show what tribe they belong to.” Last.fm claims that the more often people listen, the better the personal recommendations will match their music preferences.

Last.fm’s holy radio trinity

Last.fm’s holy radio trinity

The music service offers many different channels, like friend, neighbor, tag, and artist based radio stations. But the heart of Last.fm consists of 3 channels. One of them plays what everyone has been listening to recently. The other side of the spectrum is a ‘recommended’ music channel. It plays songs you haven’t heard before, based on your favorite music styles. “We’ve found that most people are comfortable in the middle.”

Good playlist = context + meaning

A good playlist should include context and meaning, is Hawns opinion. That’s why Last.fm users not only see which songs are recommended, but also why. They see details about the band and names of similar bands. Still, there is self critique: “I think we have great playlist, but I don’t think it’s enough.” He realizes that only radio can add real emotion to the music: “Great deejays tell you why they care about a song. They all share human emotions and understanding of their audience. No computer algorithm can match a lyrical sense of what song comes next.”

Last.fm’s music discovery tools

Last.fm’s music discovery tools

The library that people have at their fingertips isn’t limited to a few hundred songs in their personal collection. Instead, there is a search box leading to all music that has ever been recorded. Matthew Hawn: “If you’re gonna’ make sense of this world, you need to start using both of these skill sets” (technology and humanity). So how does Last.fm do this? The three main ingredients are tags, charts and interaction.

1. Tags

Last.fm uses a folksonomy approach: social tagging, instead of pre-classification of songs. It leads to tags like Things I listen to on Sunday morning. “The ones who do this, are really passionate about music – and I want them in my service.”

2. Charts

The Hype Chart is simply a list of the most popular artists on Last.fm. What’s interesting is: it’s based on plays, not on record sales or downloads. Therefor it includes artists that we haven’t ever heard of in mainstream radio formats.

3. Interaction

We all know that one-way-traffic times are long gone, because: “Broadcast is changing. If you don’t use the information you’re getting back from the audience, you’re missing something. Then you’re a broadcaster, not a content creator.”

Help listeners find music

What radio stations play, probably represents what their target audience likes most (as it’s based on music testing). But Hawn has a point when he says that a radio’s “limited playlist is not representing the full set of songs” that people enjoy to listen to. “If it was, they wouldn’t be going to places they go to now.” That sounds logical to me as well. “Help your audience to find these other artists. You can do this online. Use space in your Radioplayer, website, and social media. Invite your listeners to help you do this.”

Last.fm Vice President of Product Matthew Hawn: “Help your audience to find these other artists” (photo: Dan Smyth)

Feedback improves music scheduling

“If you give your audience a chance to feedback to you, they will amplify your playlist. Your listeners will add their personal meaning to the music and make your shows better. If you listen to them.” The Last.fm product manager makes clear that the art (human emotion) of radio will never be replaced by science (digital technology). “This isn’t art. I take my hat off for you guys who make great radio programs. I’m an American who loves coming here – because radio is more fun here than in the USA by a long shot.” [Presentation]

Add Your Comment