Loudness wars may be over between radio stations (in some markets); they go on in the music industry. Should we always ‘undo’ clipping, and if so, how?

It’s one of the questions that Bob Orban answers in the second part of our conversation. Following the history of processing, which we covered in part 1, we now focus on best practices for audio processing according to the inventor of the Optimod, reshaping radio’s on-air sound since 1975. “A lot of people fall into the trap of using processing to please themselves.”

Topics

- How to make your station sound as bright and as clear as possible (without adding more distortion)

- Why a clipping ‘undo’ function may not be the best solution to eliminate music mastering artefacts

- How to eliminate clipping distortion from over-compressed recordings outside of your processor

- Why it remains to be seen if EBU’s R128 with a target loudness of -23 LUFS is going to work

- How to achieve a more consistent sound by making less use of your automatic gain control

- How to load music and imaging into your automation system to create good audio segues

- How to integrate commercial breaks much more seamlessly with your program content

- How to make your sound appealing to older vs. younger and male vs. female listeners

- Why a signal with constant loudness matters in PPM markets (and how to achieve it)

- How to provide more ability for the PPM transmitter encoder to constantly work

“They don’t suffer from the big disadvantage of FM”

Internet stations are free of FM radio’s high-frequency pre-emphasis challenge (photo: New York Times)

Avoid over-processing your station

How loud can you go? Are we at the roof, or can it be even louder? Because everyone wants to be louder than the other guys.

(Smiles) “There’s also a thing as too loud where, no matter how clever your processing is, you sort of wash out the musical sense in what you’re doing. It’s usually just a matter of a dB or two of backing off to improve the subjective quality quite a bit.” Listening to Bob Orban’s experience in the United States, it seems like the often-criticised ownership consolidation, where many stations are being part of the same group, has at least one benefit: “The processing has been backed off a bit, and program directors have the luxury to create a sound that’s a little bit cleaner and substantially less fatiguing. That’s a good thing. A lot of the processing wars tended to be ego-driven.”

Sound loud enough everywhere

Sound loud enough everywhere

“With the ever-increasing amount of research for both programming and audio quality, things are now reaching a point where we have very good processing technology; we no longer have to compromise loudness to get a good sound. Just by not going crazy, we still have radio stations which use the potential coverage to the maximum possible extent, and we still have a something that’s nice to listen to for the audiences.”

Think of your listeners

Eventually, I guess, that’s what it’s all about?

“Yes, and audiences have plenty of places to go other than radio; they’re listening on their iPhones and desktop computers, and are starting to listen to Internet radio in the car. There’s a huge push in the audio industry to bring Internet radio to the OEM dashboard. Those transmission channels are bandwidth limited in terms of the amount of bits per second that they can push through the pipe — particularly in the US, where the mobile carriers tend to limit your bandwidth to a certain number of gigabits per month. At the same time, they don’t suffer from the big disadvantage of FM; the pre-emphasis that limits the amount of high frequencies that can be passed through the channel.”

“There’s a place for declipping, but the place is in the production studio”

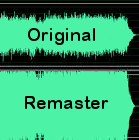

Undo algorithms in audio processors may not always work perfectly (images: Thimeo Audio Technology, photo: Thomas Giger)

Sound bright without overshoots

Clarifying pre-emphasis for non-technical readers, Orban explains that an FM transmitter is boosting high frequencies. In Europe, it’s done at 50 microseconds, meaning that at 15 kHz, high frequencies get a 13 dB increase. A radio receiver has a complementary high-frequency cut, and as a result, the overall response will be flat. FM transmitters have to put lot of high-frequency power through the channel, without overloading it. “One of the big challenges is to have good FM peak limiting, where clipping at the high-frequency end will subjectively push the absolute maximum amount of brightness through the channel, particularly with today’s records, which tend to be very bright right out of the box.”

Level with competing stations

Level with competing stations

The mastering of CD’s… wow, that’s a story of its own, right?

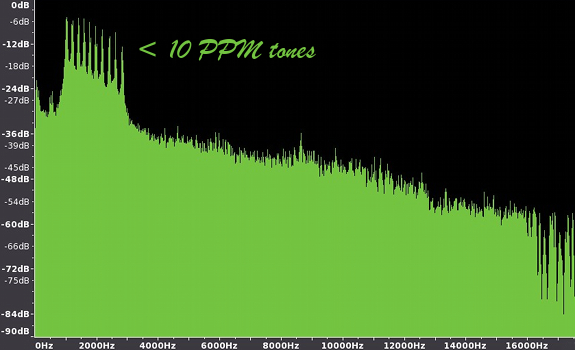

“It’s a mess. Apparently, record companies want a CD to stand out. They want their production not to be lost, a bit like the old psychology of radio; don’t fall of the dial. But the amount of clipping and processing in CDs today is just crazy; it is stuff I can’t stand listening to. You can try using declipper algorithms…”

Declip in pre-playout stage

… like Omnia is doing with the Undo function?

“Yes, I spent quite a bit of time looking at what’s available, and my opinion is: sometimes it works, and sometimes it doesn’t. Such an algorithm often makes mistakes; misidentifying stuff that has been peak-limited by some other means than clipping. If you try to de-clip that, you’re actually adding distortion to it. There’s a place for declipping, but the place is in the production studio. The guy who’s adding the original recording to the play-out system can use the declipper if it helps — but if it doesn’t help, he shouldn’t.”

“For analog FM, it remains to be seen how well that’s actually going to work”

A level of -23 LUFS would make radio sound quiet compared to what listeners are used to (image: ask.audio / iZotope)

Reduce your peak limiting

Or the guy who’s mastering the record albums can a use better education? :-)

“Frank [Foti] and I wrote What Happens To My Production When It’s Played On The Radio, about the damage that over-clipped material can cause when it’s supplied to broadcast processors.” According to Bob Orban, it’s easy to fix it upfront. “All the mastering engineer would have to do, is pull back the drive on the peak limiter chain, and run the rest of the effects. It will hardly costs anything in mastering, it’s just a question of persuading people to do it.”

Manage industry-wide loudness output

Manage industry-wide loudness output

Do you talk with record companies about this?

“Every AES, there’s a panel on this; the loudness wars are something that everybody is conscious of. It may be that Apple has finally succeeded to break through the impasse with their Mastered for iTunes initiative; a target of -16 LUFS.” The origin is found the European Broadcasting Union’s EBU R128 standard for loudness management.

Follow MPX power regulations

R128 is pushing for a ‘loudness’ of -23 LUFS, which has considerably more impact, because the difference of 1 LU equals the difference of 1 dB. “For analog FM, it remains to be seen how well that’s actually going to work, because it reduces loudness a great deal compared to what people are used to, even if stations actually obey the BS 412 multiplex power limitation.”

Program directors in Germany will not be happy…

“Probably not…”

Even if it’s a conservative radio market compared to, for example, France. Paris is one of the loudest cities in the world.

“Haha, yes.”

“Within reasonable limits, it’s not very critical how you ride a gain”

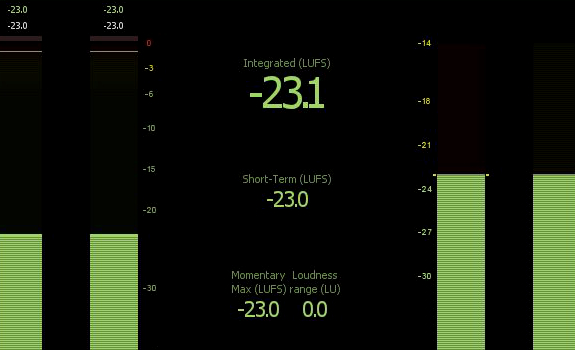

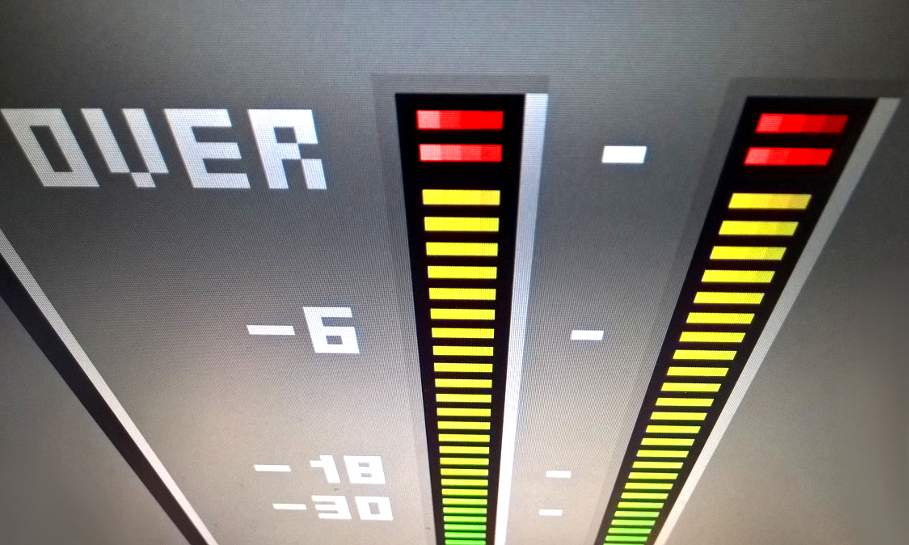

But even today’s audio processors benefit from a relatively consistent input level (image: Orban)

Don’t process for yourself

What are the factors of a great on-air sound? What are the variables that every engineer should take into account?

“Well, first of all, matching the processing to the audience. A lot of people fall into the trap of using processing to please themselves, instead of processing to please the target audience. At least in major markets, processing is a lot more researched to match it to the audience these days.” Bob Orban personally likes stations that have a clean, punchy, consistent and balanced sound, which starts by using high-quality source audio. He and Greg Ogonowski wrote a white paper about it, Maintaining Audio Quality In The Broadcast Facility (updated in 2011).

Monitor your source levels

Monitor your source levels

Speaking about balance: what do you think is a good setup of audio levels for music, imaging, microphones and phones, going from the console into the processor?

“In Europe, VU meters are not widely used; it’s mostly PPMs. But if you have a console with VU meters, a good processor and a good AGC, the processor will take care of it very well if you peak all audio material around 0 dB.”

Keep input levels consistent

He adds that program monitors based on ITU-R BS.1770 might be a bit better than VU meters when determining which source levels are being fed to the audio processor. “The whole point of a good processor is: within reasonable limits, it’s not very critical how you ride a gain, but you still do get the very best results by keeping the feed into the processor relatively consistent, so the AGC doesn’t have to go far up and down to correct things.”

“He was going for 8 to 10 hours of Time Spent Listening”

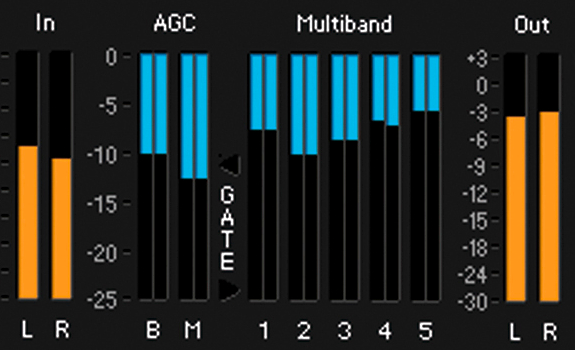

James ‘Jim’ Schulke (standing right) achieved ratings victories with Beautiful Music (photo: Dick Stout)

Pre-produce your source audio

I once worked at a station where we had an Optimod 8200. When loading music and jingles into our automation system, I made them a little bit louder at the beginning, slightly fading them back during the intro. The little peak would make the previous item sort of disappear through the processing as soon as the next item would start, so you would get smooth segues from item to item. It worked pretty well.

“Yeah, that’s really a legitimate way of doing it. Ideally, the AGC shouldn’t have to run too fast, where it starts to add compression that you might not want. By using tricks like that, you’ll take some of the load off the AGC, so that’s a perfectly reasonable way of doing things.”

Know people’s sound preference

Know people’s sound preference

You mentioned research about which sort of audio processing is suitable for which kind of audiences. Can you share some insights that you have learned over the years? What do listeners like and dislike about processing, and why?

“The research seems to be somewhat contradictory”, Bob Orban says in reference to ideas of the late James Schulke, compared with today’s practices.

Aim for long TSL

Schulke was specialised in Beautiful Music / Easy Listening, a popular FM music format during the 1970s. The mystic consultant did everything to keep listeners tuned in (which went further than his music playlist, consisting of carefully selected, pre-recorded 15-minute flow segments). “He was going for 8 to 10 hours of Time Spent Listening, and was very concerned about listener fatigue. He had specifications for every aspect of the chain; playback equipment, mixing consoles and audio processors, which were modified Audimax and Volumax. Later, he had a special modification for the Optimod 8000.” (According to sources, Schulke played ads at -6 dB, so they would never be louder than the music, and avoided high-frequency audio, as his female target audience might be sensitive to that.)

“The first thing female listeners do, is turn the tone controls all the way down”

Psycho-acoustic audio expert Bronwyn Jones backed up James Schulke’s theory (photo: Thomas Giger)

Play exclusive music material

Orban recalls that James Schulke even specified FM antennas for client stations; feeling that he could distinguish certain antennas because of differences in bandwidth and multipath interference. “I don’t know how much of this was his imagination, but you certainly couldn’t argue with his results in terms of the ratings he was getting.” In several markets, Beautiful Music stations made it to #1 in the ratings (which also might have been due to the high TSL, even with a relatively low cumulative audience). A great deal of the easy-listening playlist was instrumental music, such as instrumental versions of popular songs. Schulke would order custom-made recordings from British orchestras. “He had exclusive material.”

Use (reasonable) compression & limiting

Use (reasonable) compression & limiting

While James Schulke wanted to avoid audience fatigue — which is often said to be caused by (aggressive) processing — more recent research, published in the AES Journal, seems to tell a slightly different story. “Maybe listeners aren’t as bothered by high degrees of compression and limiting, compared to what some more ‘purist’ audio engineers think.” In fact, research indicates that people actually prefer to have some compression/limiting on the signal.

Sound comfortable for females

Most broadcast research on audio processing, apart from what’s published in AES Journals or presented at AES Conventions, is proprietary and a “competitive edge” for stations. Some “conventional wisdom” is that older audiences are more bothered by distortion and compression than younger listeners (who are used to YouTube and MP3). Bronwyn Jones, who with Emil Torick developed a loudness controller algorithm used in Orban’s TV processors, said from her perspective that “the first thing female listeners do when they hear a harshly processed station, is turn the tone controls all the way down, as the brightness and high-frequency distortion irritate them in a way that doesn’t irritate male audiences”. (Lesson learned: Schulke was right; female-oriented formats should avoid having too much treble, and rather have a warm sound.)

“Background music provides more ability for the PPM to continue to encode”

Pure talk could interrupt station identification and decrease listening credits in PPM (image: Arcane Radio Trivia)

Integrate encoding and processing

The Portable People Meter has changed the rules radio programming in PPM markets. Does it also change audio processing? Because of the PPM tones, and stuff like that?

“There’s sort of a myth that if the ‘low audio’ light on the PPM encoder goes on, it has stopped encoding, but that’s not true”, Bob Orban believes. “There’s been a push towards higher amounts of compression. It’s not that important, but program directors don’t want to see this ‘low audio’ light go on. We introduced a Ratings Encoder Loop-Through function in the 8600, so you can actually loop the PPM encoder through between the input to the stereo encoder and the output of the audio processing, so that the encoder is supplied with a maximally consistent signal.”

Ensure a consistent signal

Ensure a consistent signal

He mentions that News / Talk had some issues with the Portable People Meter technology, because it’s a bit harder to encode a speech format than a music format. There’s more silence between syllables in talk, while the PPM encoder, which is installed in the audio chain, needs some program material to mask the PPM tones that are used for the station identification. Hence the need to have a program signal with constant loudness.

Play ongoing (background) music

I heard that a presenter’s voice pitch may affect ratings, based on compatibility with PPM tone frequencies, and how well these tones can be integrated in their speech audio.

“Yeah, that’s one reason why stations have music playing all the time, even in the background while the presenters are on. Background music provides more ability for the PPM to continue to encode.” (Another reason is to maintain a feeling of forward momentum and program flow.)

“I’m using the volume control a lot”

Bob Orban’s Mark Levinson car sound system might need a compressor ;-) (photo: Lexus Enthusiast)

Look from listener’s perspective

What’s the biggest, larger-than-life radio station in terms of great sound; great processing that you have ever heard?

“Well, I have always thought that content is king. Over the years, I’ve enjoyed many radio stations. WABC in New York, the ultimate Top 40 format; KMPX in San Fransisco, the original Underground format; WOR-FM in New York, which was the original Album Rock format.” On the classical music end, he likes to listen to KDFC in San Fransisco, and WQXR in New York (“with nearly the best newscasts I have ever heard”). So although he knows so much about sound engineering, Orban likes to approach radio like an audience member: “What is there to listen to; what is the content?”

Find relaxation outside radio

Find relaxation outside radio

Do you still listen to radio a lot?

“I don’t listen that much anymore. I mostly listen to CDs in the car. I’m a classical music lover, working through complete works of Johan Sebastian Bach at the moment. It’s almost ‘so much music, so little time’. There’s a lot of stuff that I have never heard of, or heard, in the classical music arena.”

Sound good in cars

And do you listen with processing on, or do you prefer to hear it clean; as it was recorded?

“In my car, I have a nice Mark Levinson premium surround system, and unfortunately it does not have a compressor in it, where it probably really should for classical music, as its natural dynamic range is too large to ensure comfortable listening in the car — so I’m using the volume control a lot. I actually hear most of the audio processing in my lab, when I’m listening to either my processors or to competitive ones, making sure we’re competitive to what’s going on right now.”

Excellent! When a commercial station first set up in my hometown of Hereford UK, days were filled with the usual limited playlist. Just a jukebox, with annoying commercials. But there was one shining light: jazz, blues and world once a week in the evening with a knowledgeable and adventurous presenter.

The fit-and-forget FM compression did great mischief to such classic recordings, so one evening I telephoned the presenter. He took the point immediately, checked off-air, then held back the desk level – just enough to ensure frequent 100 percent modulation, but not on every darn note in the music!

Now, many years on, that station like most others has been scooped up by a conglomerate: so it’s pump pump, click click, loads of holes. But no music worth hearing either. So guess it doesn’t matter anymore.

Hi Gavin,

Thank you for your good comment, and for adding this interesting context about VU meters and audio levels – I highly appreciate it. Understanding this part of audio theory seems pretty important, so we might devote a separate article to this in the future.

I’m not an audio engineer, but I definitely agree from my on-air and programming experience that ‘it’s the loudness of the mix to the ear that is important’, as you wrote. Everything we do on the radio, is (or should be) about the listener.

Cheers,

Thomas

I’ve worked in radio and sound engineering. The problem with today’s studio operators and computer users comes from modern automation systems and digital consoles, and from a mixed up understanding of what VU meters are.

So processors are configured to deal with audio levels all over the place, from talent not watching levels or understanding them to the production guys watching peak level meters on the editing software instead of ‘listening’ with the aid of Volume Unit meters, which don’t represent the same thing. Now engineers set up the equipment, and let talent and production editors not really worry about understanding the difference in metering nor the damage it has on audio quality and consistency.

I’m happy to watch a heavily compressed audio file sit in my production software peaking around -12dBFS, and I’m also happy to watch older more dynamic content peak around -6dBFS without the need to peak normalise anything the same – as it’s the loudness of the mix to the ear that is important. That’s what VU meters were designed for.

Unfortunately, the term VU meter is now often wrongly assigned to audio level meters in general – instead of understanding how Volume Unit meters are calibrated when using analogue and digital equipment side by side, and understanding the differences between consumer audio equipment levels compared with professional broadcast equipment levels.

There’s not many articles about this fundamental difference.

Thank you, Sam! Nice to hear from you.

Hi Thomas, excellent series on broadcast sound processing. It’s all about the listener’s pleasure.

Hi Antal,

Thank you for your kind words of appreciation, they are highly appreciated :-).

That in some markets, stations with (to a certain degree) less aggressive processing can reach an up to 14% longer Time Spent Listening according to your findings is very interesting, and a point that every program director could take into consideration. Seems like James Schulke was, can certain ways, ahead of his time!

To play the you-know-how’s advocate for a second, could it be that Top 40 stations are getting away with heavy processing, because their TSL is inherently low due to format constraints (pretty high rotation of a relatively small playlist), and because sounding loud is maybe even an image enhancer for CHR?

Cheers,

Thomas

I personally highly appreciate this series on broadcast sound quality. As an AES member myself, usually fighting against the “loudness is everything” theorem, I believe that content delivery quality matters a lot. Program directors usually not rejoice when we tune the processors for a consistent, competitive AND friendly sound.

Yes! NOT over-processed / over-compressed / extreme loud sound has a positive impact on TSL. In our big data modelling algos, the measured impact is assumed between 2% and 14% (depends on the market, of course). This means a lot.

As a European AES member, I love R128 – and German stations on the FM dial do not have to worry: their – local & regional – market(s) have the same regulation, so competitors have to pull back the horses, too. Overall sound quality matters. At last!

One more point to add: my adage is “listeners come one by one, but leave in flocks”; accordingly the music production industry (“mastering” practices = clipping & other washing machine techniques) can ruin your overall sound when airing that badly sounding song on your program.

Take care when you are building your library. Listen and “look” at the songs you are going to play. Embed them between appropriate elements – Soft AC seems to be in trouble…? :)

Cheers,

Antal