Audio processing is not necessarily about being the loudest. First and foremost, you should complement your on-air presentation, and match your programming mood.

After starting our radio sound processing series with Orban and Omnia, we now meet Mike Erickson of Wheatstone Audio Processing for a good talk about how quality WAV + linear STL help you achieve longer TSL + higher PPM! And how less = more, especially when you don’t have a huge budget. “I’ve never heard a listener complain that a station was not loud enough.”

“You were stretching the analog soup

as far as you could”

Back in the day, radio stations had a whole chain of audio processors for their on-air sound, until Orban developed some of the first all-in-one boxes like the Optimod 8101 multi-band processor (photo: YouTube / Kleine Braut)

Create an audio chain

When Mike Erickson was helping smaller radio stations to improve their on-air sound, early in his career, he sometimes had to find both innovative and low-cost solutions. “I used to look for pre-processors that are flying under the radar – cheap multiband compressors or automatic gain controllers, which created certain effects that most people wouldn’t know about. I also scoured eBay, and searched in radio station closets for old broadcast processors to fix them up and put them on air. I was successful at making old stuff sound pretty good, compared to digital Omnia 6s and Orban 8400s.” He later became an audio engineer for CBS Radio in New York, and currently is a support engineer for Wheatstone Audio Processing.

Combine multiple processing devices

Combine multiple processing devices

He sees the Orban 8000 in 1975 as the first evolution. It managed to combine a wideband gain control device, pre-emphasis limiter and stereo generator and make it work as a system. When Disco music (powerful bass) became popular, wideband gain reduction was no longer ideal: “Some partially solved that problem by placing multiband processors in front of the 8000, but it wasn’t truly cured until the Orban 8100 with its split-band processing.”

Develop digital processing innovations

Erickson recalls that in the 80s, stations used to have several processors in a row: “To get more loudness, you were stretching the analog soup as far as you could”. This started to end with digital processors, like the Orban 8200 which had a 2-band AGC and a 5-band compressor/limiter, and the Cutting Edge (now Omnia) Unity 2000 model that had a wide-band AGC, followed by a 4-band AGC and a 4-band limiter. “Unlike separate processors in front of the main one, these sections work together as a system in one piece of hardware. That’s where processing has really been moving as far as the structure of how it works. Nowadays, of course, manufacturers like Wheatstone take audio processing one step further with new digital signal processing advancements.”

“By guesstimating the original signal levels,

you’re unmasking the final limiting products”

Re-creating disappeared dynamics may cause hard limiting harmonics to appear (images: Pro Tools, Waves)

Adapt processing to necessity

A common problem is excessive composite clipping, which Wheatstone solves by putting automatic gain control intelligence in a side chain. “A lot of processors use wide-band AGCs in the signal path. Sometimes you hear them work, like low passages that rise up unnaturally.” Mike Erickson explains how their own side chain automatic gain control works. Incoming audio will first go through input conditioning (including a low-pass filter, phase rotator, balance control and gain control), and the output of that is split. The main signal continues to a 5-band AGC compressor, while the side chain goes to a signal analyzer that sends data to, and receives data from, the 5-band processor. The analyzer will then slow down the processing when the audio has limited dynamic range.

Avoid unleashing maximizing artifacts

Avoid unleashing maximizing artifacts

In his opinion, one should be careful with restoring lost dynamics of over-processed music by reformatting sound waves, like some manufacturers do. “The problem is that when you have added dynamic range by guesstimating the original signal levels, you’re unmasking the final limiting products of the mastering processor. The waveform may look prettier, but the harmonics from that hard limiting are still in that product.”

Keep an open sound

According to Erickson, their SST AGC algorithm not only handles dynamically challenged audio material. “It also helps with transitions from cut to cut and from source to source, especially when their levels are very different. It can quickly catch up, but it doesn’t sound like catching up. It will raise the average level of softer parts of a song, like a soft piano, but not to the point where you hear clipping artifacts. It tries to keep an appearance of dynamic range, while maintaining a high level of average modulation. Because we don’t use expanders, the body of the music remains and it still sounds open.”

“Other stations sounded like

they were lost inside the radio”

Z100 had a powerful yet authentic sound, that set them apart from other New York stations in 1983 (image: Z100)

Experiment with processing setups

You’ve been with CBS Radio’s The FAN as well as Oldies format CBS-FM, both in America’s number 1 market. Can you tell us a bit about the processing wars in New York?

“I was working for WCBS-FM between 2007 and 2010, after it had switched back from the Jack FM format. At that time, CBS-FM had an Optimod 8500 with a TransLanTech Ariane leveler in front – a device that the other CBS stations in New York used as well. I had installed another ‘secret’ box in front of the Ariane, to give the audio a little extra punch”, says Mike Erickson. “I loved the Orban, but a year later Wheatstone came out with one of their first FM broadcast processors, the AP2000. We tried it on the air, and it sounded unbelievable. But I couldn’t get budget to buy it, because I just got the 8500 a year before.”

Sound loud but real

Sound loud but real

The real loudness wars took place in the 1980s when Z100 came along: “PD Scott Shannon wanted to sound larger than life and different from anyone else that was ever heard there.” The engineer grew up with New York radio as a 10-year-old kid. “Z100 sounded very real to me; very close to the records that I was buying. The other stations sounded like they were lost inside the radio.” He attributes the success of Z100 in 1983 to a combination of factors:

[audio:http://www.radioiloveit.com/wp-content/uploads/mike-erickson-wheatstone-audio-processing-interview-thomas-giger-01.mp3|titles=Mike Erickson of Wheatstone Audio Processing about Z100]

Reflect content in sound

“What they did, was make the audio processing part of a bigger picture“, he continues. “As good as your processor may be, it’s your programming and talent that makes it shine.” Looking at today’s radio wars, Erickson feels like the rise of station clusters (where one operator owns many brands in the market) did not contribute to creative audio processing. They often share the same studio facilities and the same technical setup. “In the eighties, every station had to make its own way. Today, it seems like most of them want to sound like the other guys, instead of standing out.”

“Calibrating everything is a big key”

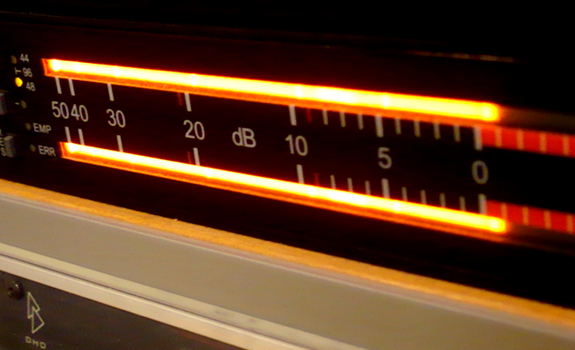

Instead of focusing on the processing rack, radio engineers should have a careful eye for all aspects of their audio chain and sound processing – from broadcast mixer output to FM transmitter site (photo: Thomas Giger)

Build linear audio chains

Wheatstone processors are being used in markets like New York, Houston, Philadelphia and Miami. Mike Erickson recently had a chance to set up the on-air sound for Rhythmic CHR Hot 104.7 in Portland, Maine. The station’s new Vorsis AirAura X3 processor came along with a new mixing console, a clean STL path, a new transmitter, and new antennas. Hot 104.7 does now have a completely linear signal route, one of the reasons why he’s very happy with the end result. “It has basses and highs that sound absolutely amazing.”

Use linear audio files

Use linear audio files

In a time when hard drives were expensive, there was a “very, very, very bad trade-off” between quality and compression by using MP2 and MP3 files. The advice is to replace inferior sound files by linear source audio (like WAV). “It’s one of the biggest steps you can take to improve your sound, regardless of the processor. When you feed any processor non-linear and compressed audio, it’ll never sound as clean and loud as you want it.”

Have STL bandwith flexibility

Another important thing is to execute regular preventive maintenance on the entire audio path. “Every part of that chain plays an important role in how the station sounds.” Erickson explains why studio-transmitter links make a huge difference. Unless you have to use audio-over-IP codecs if your transmitter site can’t be reached by RF connections, you should use a linear connection. “The more linear your chain, the better your sound. Have enough headroom in your STL, so you’re not running out of it when a sloppy operator overloads the mixing console. Calibrating everything is a big key.”

“Sound processing should

complement your on-air presentation”

If Magic 105.4 in London would suddenly use aggressive audio processing, it could affect their Time Spent Listening as the on-air sound would not fit their warm AC programming mood and brand image anymore (images: Bauer Media)

Prioritize audio processing optimization

What are the main ingredients of a great on-air sound in terms of your processor settings?

While factory presets can be a great start, Mike Erickson advises to mainly listen to how a preset sounds, and basically ignore the name. Presets are often generic settings for formats such as CHR, Rock, Oldies, Classical and News-Talk. “If you have an AC station, the Country preset may also sound good for your AC station in your particular market.” Another useful tip is to change your sound with only one, small thing at a time. “If you think: the main problem is that it’s not loud enough, but I would also like more bass, first try to get it a little bit louder. Once you’re satisfied with the loudness, see if you can add a little more bass. If you do two or three things at the same time, you’re going to end up in the weeds.”

Make sound changes carefully

Make sound changes carefully

Which other components are important in setting up your audio processor the right way?

“We have a saying here that if it sounds good, it is good. Audio processing is very subjective. Always be mindful that what you add in one place, will make something work harder upstream. If you’re adding more bass in the front-end compressor, the back-end bass limiter has now changed.”

Complement content and image

How do you experience working on station sounds with program directors vs. audio engineers who have a technical background like you do?

Erickson understands that programmers see aggressive processing as another way to stand out and get noticed, but advises them to ask themselves: “Is this sound appropriate for the format I’m playing, for the listener demographic I’m going after, and for the environment that people will be listening in?” He feels like PDs are carefully thinking about promotions, imaging and music, but sometimes fall short in processing. When a station is very listener-friendly, except for an aggressive sound, it will have an adverse effect on TSL. Conversely, too light processing on a highly energetic station conveys the wrong message as well. “Processing should complement your on-air presentation, and match your programming mood.”

“It will make the whole station sound better”

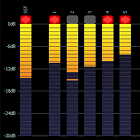

Consistent source levels help the audio processing achieve a more consistent on-air sound (photo: Thomas Giger)

Have a sound policy

Can audio processing have an effect on PPM ratings?

“There’s a lot of misconception about processing for PPM. The main problem is making sure that the audio level doesn’t fall below a certain threshold, so that the encoders keep working.” Erickson suggests radio stations to have a standard set of reference levels for various audio sources as a guideline for board ops and audio producers who load songs, jingles and spots into the automation system. In addition to play-out sources, voices of callers and presenters going to an editor like VoxPro matter just as much. Separate processing on the DJ and caller voices can help to balance their levels. “It will make the biggest difference in the world for making a station sound tight – every cut being right there; nothing being over-modulated. You can then run the board without worrying about your levels because everything has been set.”

Check meters & faders constantly

Check meters & faders constantly

Board ops and self-support presenters should be mindful of the meters as well as where faders are being placed – so that, for example, microphones are not much louder than the rest. “To be very careful with console levels helps with PPM encoding and allows the processor to do a better job, because it’s not constantly fighting various input levels from source to source. It will make the whole station sound better.”

Keep source material clean

Erickson has the following tips for a radio station’s audio file management policy:

• Import music tracks exactly as they have been mastered. “You don’t need bass enhancement or equalization, as the processing is going to do that down the line.”

• Keep EQ buttons on your mixing console neutral when dubbing audio into the automation system. This ensures you don’t add anything to the original by accident.

• Keep preprocessing, like normalization and limiting, to a minimum. “Bring the peaks down, but don’t squash the dynamic range.”

• Use consistent reference levels for recording or processing audio files when dubbing them into the automation system. Limit peaks to -15 and keep the average level at -20 dBFS.

• Keep play-out signals below 0 dBFS on a digital broadcast mixer. Board operators should realize that signals above 0 dBFS (digital) create distortion, as they are different from 0 dB (analog).

• Bypass input level and balance controls on a broadcast mixer. “The tools board ops need to get the job done are very limited – and they should be.”

“Create content that’s compelling to listen to

without any processing”

Mike Erickson (sitting in the middle, between his colleagues Jeff Keith and Steve Dove in their processing lab) thinks that radio stations with less resources could purchase older processors online, and focus on a listener-friendly sound and interesting content rather than trying to keep up with the loudness war (image: Wheatstone Audio Processing)

Keep audio productions dynamic

Mike Erickson points out that we should “produce stuff that sounds good on the radio in context with everything else, and not like a sea of noise because somebody in production has already squashed it.” He has the following tips for creative directors who produce station imaging and spots:

• Let your final mix sound open and natural in the production studio. “More dynamic range will actually result in more impact on the air, especially with percussion and effects.”

• Avoid too much stereo enhancement in your productions. “Left-right effects and stuff like that might end up being out of phase on mono receivers or sound ugly on the air.”

• Play back imaging elements and radio spots through a separate audio processor in your production studio to simulate how it will sound on the air, and make necessary adjustments.

• Educate advertisers & agencies to deliver commercials as a linear audio file such as WAV (instead of MP3) to get their message across better, and get more return on investment.

Create an authentic sound

Create an authentic sound

What do you see as the next big thing in audio processing?

“Making FM radio sound more transparent, by getting closer to the source. We should try to get rid of the sonic signature of pre-emphasized audio, and to let the processing work or relax depending on what’s needed.” He’s not a fan of expanders: “They make some stuff sound very dynamic and open, but on other stuff it sounds like the audio can’t breathe.”

Offer sound & content quality

What if you’re not in New York, but at a local station in Long Island or at a community station in South Africa with no budget to buy the newest Orban, Omnia or Wheatstone processor?

“When you don’t have a lot of resources, less is always more. When they’re looking for something to listen to, listeners may stop at a loud station over a soft one – because there’s a perception of louder, stronger, bigger, bolder – but I’ve never heard a listener complain that a station was not loud enough. I have heard people complain that a station is too loud, too shrill, too bassy, or too aggravating.” Erickson’s advice for working with an older processor is to not compete with newer models that have more horsepower: “Try to create a nice, open, friendly, inviting sound and content that’s compelling for people to listen to without any processing.” Our mutual conclusion is that processing is part of a bigger thing – a living and breathing radio station, that’s connecting with listeners in a unique way:

[audio:http://www.radioiloveit.com/wp-content/uploads/mike-erickson-wheatstone-audio-processing-interview-thomas-giger-02.mp3|titles=Mike Erickson of Wheatstone Audio Processing about radio’s mission]

Hi Thomas,

So which low budget solution do you recommend for a home studio?

I understand an elder processor as Optimod 8101B would be fine, but rarely to find as far as I know. Or is there something better to start with?

Hey Scott,

Thanks for your reply, glad you’ve found it at a good read, and thanks for your tip on using FLAC files instead of WAV for an even better sound!

I agree with you that in the end, it’s all about your music – and your content, plus your personality / entertainment factor (which separates radio from Spotify, Pandora and someone’s personal music collection).

Cheers,

Thomas

Hi, this is a good article.

I agree that source material is a major key to sounding good on the air, it is akin to GIGO – Garbage In, Garbage Out. We use FLAC as opposed to WAV, and have found it to be a better medium for storing audio and play-out files.

One other thing, often overlooked, is that your average person just wants to hear the songs they prefer. So no matter how clean and good you may sound on air, if your programming sucks, the audio processing simply does not matter at all.

I have seen first hand an AM-LW station beating the pants off great-sounding FM stations in a major market, simply because the audience they played to loved the music and variation of their programming. No silly People Meters to make a corporation FAT either :-).

Best, Scott

Hi Lloyd, great that you’ve managed to figure out a lot yourself, and that you have your radio station on air! If you could describe in a bit more detail how your music categories and song rotations are currently set up – and also what your exact goals are – we’re happy to see how we can help you.

After a year learning with no help and first time in this field, finally on the air 1:00 to 10:00 PM with my Internet radio station. I am playing variety hits at the present moment. I need help with the format.

Excellent. We use AirAura X3, and the sound of our radio station is amazing. Thanks Mike, for all the support.

Great summary, very useful viewpoint; every COO or PD should read this!

Broadcast processors and final sound design should be considered as important as the content itself: listeners do not like an overprocessed sound.

I disagree with some points, but the core message “deliver and maintain a competitive and good sound quality” is right – we practice other methods and rules, but anyhow the outcome matters.

Best,

Antal