Good radio research depends on great source material, consisting of the right audience sample that is leading to valid & consistent data to spot long-term trends.

Part 1 of our expert talk with Stephen Ryan of Ryan Research was about a strategic focus on audience segments (like female listeners) to build a loyal following and consistent ratings. In this second part, we cover the necessity to use a high-quality sample for reliable data, and then look for long-term trends in your research. “The real test is consistency.”

“A helpful starting point

for a busy program or music director”

A management sheet offers advice for song category placement based on music test results (image: Ryan Research)

Test only familiar songs

Is it possible to test unfamiliar songs, like new releases?

“Some companies are trying to pretest songs. One way is to simply play the song and ask people if they think they might like this, similar to callout [CATI-based interview, TG]. Another way is specific analysis of social media activity to see how many times an artist or song has been mentioned. It can be a useful guide for record companies and program directors. The difficulty is that there are songs that you hear for the first time, and don’t really like yet. After a period of time, you might go: ‘actually, this is pretty good!’ You have to do longer-term testing to see that.” He’s read a report from a Scandinavian research group that cross-tabulates many PPM reports and broadcast playlists to see which songs people seem to like, based on their tune in & out behavior. “That’s interesting, but you’re still judging something that’s already gone to air. Somebody still has to make a decision to play something, initially without any of this stuff.”

Focus on radio listeners

Focus on radio listeners

Ryan once worked with an AC station that did live shows around the country, having local bands on stage. As visitors were excited and even stood in line for artist autographs, a sales guy asked why they didn’t play these artists on the radio then. “I said: people love to hear this music here and now, in this live environment, but also at 10 o’clock in the morning? Not necessarily. You need research to understand how songs work in a radio environment.”

Monitor long-term song developments

So, context matters. Do you just deliver a spreadsheet full of numbers, or do you offer music directors suggestions like: you could move this song to the A list, and put that one in Recurrent?

“It depends on the client. Most of the time, I’m not living in the market, so I don’t know what’s going on there all the time.” He provides what he calls a “management report”, showing all songs on the playlist, marking those that have been tested. The large picture above is a mock-up of a part of such a report. Clients get an overview of every song’s life cycle from the moment it was added, including the number of spins, the latest research scores, and what competitors are doing with it. “I also make recommendations as to why I believe certain things should happen, like ‘this should be a power; this should be a secondary; this should go to Recurrents’. It can be a helpful starting point for a busy program or music director. I then see the report coming back with what actually happened. A lot of the time, we’re on the same page, and sometimes they make a different decision. But they’re in the market; they know more than I do.”

“With 60-70 plays a week,

you’re starting to push your luck”

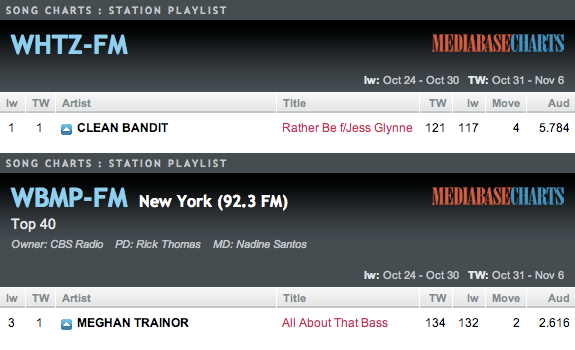

European audiences are not used to the power current exposure on 100%-CHR stations like Z100 and its competitor 92.3 AMP Radio in New York, which play their top hit song up to 134 times a week (images: All Access / Mediabase)

Keep rotations within reason

Song rotations are always a nice discussion. Mediabase Charts reveal that CHR stations in New York play their power currents as much as every 48 minutes!

“That’s been very specific for America for quite some time. If you’re rotating songs that much, you’re going to burn them quickly. I haven’t worked in a market where you can get away with that yet.” Stephen Ryan feels like European stations have a tendency to allow songs a longer life span than just a few weeks, which he finds a good thing for this radio market. “With 60-70 plays a week, you’re starting to push your luck. In the States, you will get pure CHR stations. In Europe, stations who call themselves CHR tend to be more like a Hot AC, in terms of rotations. A lot depends on the population size. With smaller populations, it’s difficult to base your audience on cume only. In order to build greater total listening, TSL needs to be considered. You may also need to broaden your target demo, like trying to bring in slightly older listeners. They tend to be more adverse to higher rotations.”

Reach your full potential

Reach your full potential

They may have a CHR image, but not a song rotation like Z100 or AMP.

“Yes, there are lifestyle and branding issues, versus what actually happens on the air. Advertisers should be taken into account as well. If you think of your population base, you may have not enough people in the area to be totally focused on a young audience, which comes in to listen to a song that being played 100 times a week, or whatever.”

Use relevant research methods

What’s important to consider when planning music research for a radio station?

“There are strategic elements that have to be looked at first. Where are you in the radio station’s life; are you a new or a heritage brand?” Ryan says it also matters what you want to achieve; if you’re maintaining your current position or defending yourself against competitors. It will determine your approach. “Then the question is: do you have a realistic budget? Usually, the answer is ‘no’, haha. Then you have to say: what can you do?” Once the strategic objectives and available resources are agreed upon, it’s time to look at the format in detail: “The more reliant you are on currents & recurrents, the more you will rely on call-out. If you have an oldies-based format or play mostly familiar music, then you might be looking at an auditorium music test. Then you have to consider: how many of those can you afford? Doing an AMT is great; it might fix a problem now, but the results are only valid for a couple of months – not so much for the older songs, but for more recent stuff that might be borderline-burned. A lot can change within 3 or 4 months.”

“Online makes access a lot easier,

but there are plusses and minuses”

Online music testing still requires careful panelist recruiting and data integrity checking (image: Sky Radio Group)

Focus on careful recruiting

What about online music testing as an alternative for expensive auditorium music testing?

“AMTs and callouts are expensive because you’re recruiting a specific sample of a specific demo. Those people should listen to certain stations, including you and your competition. You can do the test online, but you still have to recruit those people.” He explains that to find 100 participants, you may have to call 20.000 people, as many are not available, not interested, or not qualifying. Simply asking P1 listeners to go to your website and letting them grade some songs is not a good idea: “It’s like in the old days, when people were calling in for requests. That’s not what you want to program a station on. You need to encourage a high-quality sample or you are wasting your time – and could even cause a lot of damage. Bad research gives bad results; gives disastrous consequences. You have to make sure that your data are reliable.”

Manage participants in panels

Manage participants in panels

Participants can be found in many ways, from hiring field workers to buying complete databases. Stephen Ryan’s advice is to let people who qualify join a panel. “Once they are in a panel, they are manageable, and you can send them a consistent message. People have to jump through some hoops to join; they can’t just go to your website and play around.” There is another aspect that is also really important for online music panels.

Ensure research data validity

“You need to do a serious data integrity check. The last thing you want, is your competitor radio station’s staff filling up your panel, and giving you all sorts of interesting results, haha. Online makes access a lot easier, but there are plusses and minuses. The idea of having an AMT with 140 people sitting in a room at the same time might be accused of being a bit archaic, but on the other hand: you can see them and you know exactly what they’re doing.” He mentions several ways of quality control for online music testing. One is to rule out straight liners; people who repeatedly give the same score to many songs in a row, compared to most of the rest of the panel. Another way is time monitoring, and disqualifying people who get half way (or finish) a test much faster than the average person. His company is also using “some proprietary tools” in the form of algorithms to highlight certain outliers. “You know your data integrity is good enough when you see consistency, because then you’re able to spot trends.”

“You don’t want them to be

distracted from the music”

The amount of perceptual questions asked during an auditorium music test should be limited (image: Thomas Giger)

Choose scales over dials

Which method do you prefer for letting people rate songs in an auditorium music test?

“I use a 6-point scale. It starts at ‘favorite’ and goes all the way down to ‘unfamiliar’. If a song is unfamiliar, people shouldn’t be rating it, as the purpose of an AMT is testing familiar music. If you get a high number of unfamiliar scores, then you have been testing the wrong songs. You should only test familiar songs at an AMT. An unfamiliar song is a wasted slot on the list. If you want to do something with unfamiliar songs, you should use callout or another method to quickly see how a song is developing.” AMT facilities often use electronic devices where people can turn a dial from 0-100% (where all up means ‘fantastic’, and all down means ‘not great’). Ryan is not a fan of dials, because the scores are too open for interpretation. For example: does a lower score stand for ‘dislike’, ‘burn’ or something else?

Trigger specific audience feedback

Trigger specific audience feedback

He mentions a possible “phantom report” of the following song when using the so-called prefalyzer dial in an AMT: “A great song comes on. People love it, and whack the dial to 100%. If they don’t like the next song at all, they might only bring it back to 40%. I favor a 6-point scale to get a decisive answer from somebody. If a song is negative, is that because it’s burned? Did they actually ever like that song in the first place? That’s important to consider.”

Test your station images

During auditorium tests, do you only test music – or do you also do additional radio research?

“We do include perceptional questions”, Stephen Ryan says. This is possible because AMT groups are based on quotas: “Every person in the room should have listened to you in the last week. Half of them are your biggest fans. Then there are people who also listen to your competitors.” So even if an AMT is about judging songs, there is room for open questions to get a sense of how people might feel about your station and others. When testing 600 songs, there should be a coffee break after 300 songs, and a short break in the middle of each half. Before or after a break is a good moment to ask some perceptional questions, provided it’s not too much. “You don’t want them to be distracted from the music.”

“There shouldn’t be

massive variations”

When music test participants are split into similar audience groups with the same demographic composition, there should be overall consistency (and limited deviation) between scores for certain songs & artists (photo: Marco Maas)

Shuffle your song hooks

How important is getting the right hook for a music test? Do you ever do a split test, like playing hook A to one half, and hook B to the other half of the participants?

“We do in certain circumstances. It would be difficult to do in an AMT, because the hook is the hook, and you’re dealing with very familiar songs. They should be judging a song because they know it. What we can do, is flip the lists. During the last 100 songs, most people are getting tired and are not scoring as carefully as they did at the beginning. Split your AMT over a couple of nights, and shake up your songs every time. It’s a bit of a nightmare to join it back together, but it means there’s no list bias. Unless you have the exact same audience composition each night, you might see some variations, but there shouldn’t be massive variations where certain types of people first love Bryan Adams, and a day later say the exact opposite.”

Split your research population

Split your research population

Ryan likes to divide auditorium music tests in at least two sessions with similar groups, as a small group can be monitored more carefully. Another reason is that sitting in between 140 people might intimidate some people. “It shouldn’t feel like an exam; it should be fun. We do various things, like getting them to stand up in between, when we are giving away prizes and that kind of stuff. It’s a nice way to spend the evening.”

Keep station names anonymous

He prefers to do a blind AMT to avoid any bias that the station name might cause among participants, who vary from huge fans (P1 audiences) to occasional listeners who have another station as their first choice. “They are told that it’s to improve music on the radio in city X or country Y.” The auditorium should be filled with participants who don’t know each other, so rule out other people from the same household (who might influence each other). Instructors should emphasize that there are no right or wrong answers, and that the goal is simply to help radio stations play better music by providing them with honest opinions.

“Online and digital

does bring some problems”

While digital and mobile devices make it easier to reach participants, they might be less patient with longer surveys because of the shorter attention span that’s connected to people’s user habits / online behavior (photo: stock image)

Respect people’s attention span

Research methods for music radio are the same for many years now; we have callout, auditorium and online testing of songs. What do you see as the future of radio research?

“Definitely online and digital. As it affects everything else, it will affect research as well. It may remove some costs, as it’s easier to access people, but it does bring some problems. For example: how many songs are people prepared to listen to on a mobile phone, and how much time will they give you?” Based on generic user data, Stephen Ryan suggests to keep laptop questionnaires under 20, and mobile surveys below 7 minutes. “With a laptop, more than likely somebody is sitting by himself in an isolated area. With a mobile device, you have absolutely no idea where someone is and whether he’s alone or not. So you don’t know if you get truly that person’s response, or of several people.”

Try new research methods

Try new research methods

Saatchi & Saatchi’s Feel The Reel biosensor wristband to measure people’s emotional response to content could be interesting for music research as well: “But do you want somebody to sit there for two hours, listening to music, without doing anything? And if you give them something to do, like reading a magazine, their emotional response could be caused by a sexy article, and not the song hook that they were listening to at the time.”

Look for consistent patterns

Are you also testing complete radio shows to analyze how listeners respond to certain content?

“Some researchers use a form of dial-based methodology where they play content, and participants decide on a scale as to how interested they are in it. You can see that as certain things are mentioned, the graph goes up or down.” Similar research has been used on political speeches. However, it focuses on ‘policy’, which, if popular, can be repeated. For radio, Ryan warns to never jump to conclusions based on single incidents. “If you just look at one topic, it could be great today, but die tomorrow. Rather search for longer-term trends, like when something happens with a similar piece of content again and again. No matter what type of research you’re doing on an on-going basis, the real test is consistency. You can expect some fluctuations, but if your results are spiking all over the place from survey to survey, then there is something wrong with your sample and/or your methodology. Consistency gives you trends that make sense.”

[See also part 1: Radio Programming Should Avoid Any ‘Chalk & Cheese’]

Add Your Comment